If you’re just tuning in, this is a continuation of the Startup Intellectual Property Checklist series. Intellectual property is key to the success of a technology startup. But, what is intellectual property? How do you protect it? What about the intellectual property of others? This checklist provides a basic primer on key intellectual property issues each founder should understand, and a simple To-Do list of action items. Part 2 will feature items 4-6, so stay tuned for future posts.

STARTUP INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY CHECKLIST

Part 1

1) Get All Founders to Assign Intellectual Property to Company

3) Budget & Funding for Intellectual Property

Part 2

4) Trademark Registration

5) Copyright Registration

6) Patentable vs. Infringing – Know the Difference

Part 3

7) Design Patents vs. Utility Patents – Choose the Right Filings

8) Patent Search – Find Out What’s Patentable

9) Provisional Patent Applications

Part 4

10) Nonprovisional Patent Applications

11) Slogging Through the Patent Application Process (aka “Patent Prosecution”)

12) International Patent Protection

____

4) Trademark Registration

Picking your company name, brands for your products and services, and associated taglines can be difficult. Undoubtedly, you are already thinking about distinguishing your startup from the competition. It’s never too early to consider trademark registration because the purpose of a trademark is to identify the source of a product or service. A trademark is typically a name or logo that lets purchasers know that what they’re buying comes from your company and not someone else.

Registering your trademarks with the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) gives you nationwide rights, though you still need to be wary of any unregistered common law trademark owners who may have used a similar trademark before you. It’s not necessary to apply for a trademark in order to start using it, but the cost of filing a US trademark application is so low that it’s not worth skipping the application just to save a few bucks.

There are at least three factors to consider before filing a trademark application:

1) Has anyone already filed for a similar trademark? Notice I did not say identical. While you can search USPTO filings for yourself at www.uspto.gov, keep in mind that you want to uncover any similar marks. Our law firm includes a free USPTO search as part of our initial filing process.

2) Is your mark descriptive of the products or services offered? This takes into consideration the meaning of your trademark in relation to the products/services offered. Obviously, one could not register the term “APPLE” for the actual fruit since that term is generic in relation to the product. A mark may be considered merely descriptive if it describes an ingredient, quality, characteristic, function, feature, purpose, or use of the specified goods or services. This is a gray area where insight from an experienced IP attorney can be useful.

3) Should you apply for the trademark before or after using it? Assuming your trademark clears the above two hurdles, then you should file for your company name at or near incorporation, and for your product names and logos preferably before launch. I generally recommend filing an Intent-To-Use (ITU) application before launching the product/service. This prevents third parties from filing before you as soon as they see your mark. An ITU trademark application also provides significant legal advantages if the application matures into a registration as your trademark will be regarded as if it had been used as of the filing date. There are additional costs associated with ITU applications, but those costs are far outweighed by the benefits of an earlier use date.

Several online trademark filing services purport to help, but I don’t see the point of using a middleman who can’t help you navigate through the above factors. You should either use an experienced IP attorney who can, or file the application yourself at www.uspto.gov.

5) Copyright Registration

A copyright registration can be a powerful weapon against copycats. The trick is to register your works prior to copying by others. This will enable you to recoup attorney’s fees and monetary statutory damages against a copyright infringer. If possible, apply for copyright protection while the works are unpublished (i.e., prior to distributing copies to the public).

Keep in mind that concepts and functions are generally not protected under copyright law. If your idea is functional in nature, consider patent protection.

What if you have several copyrightable works to register? Under certain conditions, you can file a single copyright application with the US Copyright Office to cover multiple works. You can also apply for group registration of certain works, such as daily newsletters, contributions to periodicals, published photos, and more.

6) Patentable vs. Infringing – Know the Difference

You can’t afford to be ignorant or wrong about the distinction between patentability and infringement if you are in the technology business. I find that many new clients have a misconception about what patents can and cannot do.

To be patentable, an invention has to be unique over the prior art, a term that generally refers to what’s already out there. Basically, your invention has to be sufficiently new and “non-obvious” over what has already been invented. Infringement, however, focuses on whether your product or service includes each feature/element recited in at least one independent claim of the patent.

So, is it possible to infringe someone else’s patent with your own patented product? Yes. Your patent does not protect you from infringement. A patent only gives the owner the right to exclude others from practicing the patented invention, but a patent does not give the owner the freedom to use the invention.

While it may seem twisted at first, the logic makes sense once you think it through. If you get a patent for improving upon an existing idea, what about the rights of the inventor who patented the original idea?

Some hypothetical examples may help illustrate the difference:

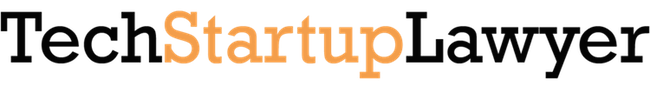

Example 1: Suppose you invent a combination of features ABCD, and a prior art patent discloses and claims the combination ABC. This example shows how you can obtain a patent and yet infringe someone else’s patent.

Result:

Patentable? Yes, because your invention includes a new feature D (aka point of novelty) that is not disclosed in the prior art.

Infringing? Yes, because your product includes all three features claimed in the patent.

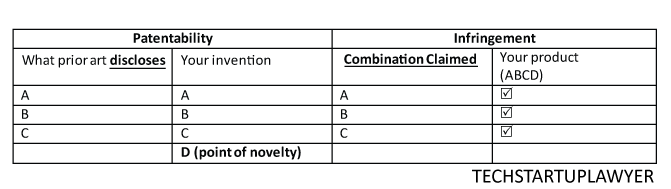

Example 2: Suppose you invent a combination of features BCD (no A), and a prior art patent discloses and claims the combination ABC.

Result:

Patentable? Yes, because your invention includes a new feature D (aka point of novelty) that is not disclosed in the prior art.

Infringing? No, at least not literally because your product omits at least one feature in the claimed combination. Doctrine of equivalents may still come into play as a backstop to literal infringement.

Therefore, how you read a patent depends upon whether you’re concerned with patentability or infringement. If it’s patentability, then you’ll want to focus on the drawings and accompanying written description, and see if those disclosures show each feature of your invention. If it’s infringement, then you’ll look to the claims, and see if your product omits at least one element of every independent claim, both literally and under the doctrine of equivalents (this gets tricky, so always consult your patent attorney).